Featuring

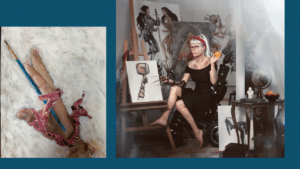

Stephanie Buxhoeveden , Nurse Practitioner & Lydia Emily Archibald , Street Artist and Person Living With MS

Close

30 Aug 2023 | ~29:48 Engagement Time

Meet street artist, rebel, and progressive MS warrior Lydia Emily. She shares her life with us including the story of her MS diagnosis, adaptations she made, and some stories and experiences from creating art. Lydia Emily’s approach to her MS is real and refreshing. She sees strength in seeking out adaptations, asking for help, and making the adjustments needed to live a happy and easier life with MS. Keep your eye out for Lydia Emily’s upcoming book The Art of Hope. You can learn more about Lydia Emily and her art via her website – https://lydiaemily.com/ and her Instagram @lydiaemily.

Artist, Rebel, and Progressive MS Warrior

Episode 146 – Podcast Transcript

[Music]

[(0:18)] Stephanie Buxhoeveden: Welcome to the Can Do Podcast. I’m your host Stephanie Buxhoeveden. I live with MS and I’m a clinician and MS researcher. I am very excited to welcome our guest, Lydia Emily, who’s an artist living with progressive MS. Welcome, Lydia.

[(0:34)] Lydia Emily: Hey, thanks for having me.

[(0:36)] Stephanie: Absolutely. Can you start by just telling us a little bit about how you were diagnosed and how long you’ve been living with MS?

[(0:43)] Lydia Emily: Oh man. I think I was diagnosed with MS in 2010 maybe. Man, that’s a tough question. I’m sorry.

[(0:51)] Stephanie: That’s okay.

[(0:51)] Lydia Emily: I have a manager someplace. There’s a manager somewhere. We can ask someone. We can, we can fact check it but it was probably like 12 years ago. 11 or 12 years ago I’m guessing, that feels right. Like I feel like we had a 10-year anniversary maybe over COVID. So I’m just gonna, I’m just gonna stick with that. Like it-

[(1:09)] Stephanie: Yeah. I just celebrated my 10-year anniversary with it.

[(1:13)] Lydia Emily: Oh, cheers.

[(1:15)] Stephanie: Cheers to that. So-

[(1:16)] Lydia Emily: That’s awesome. So I was, um, do you wanna hear the story or no? I mean, I don’t have to tell a story. You do. Are you sure?

[(1:22)] Stephanie: Yeah.

[(1:22)] Lydia Emily: I can talk. I can just talk forever.

[(1:24)] Stephanie: Yeah. I love it.

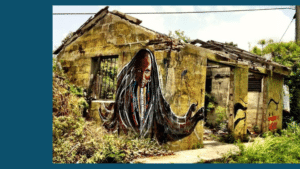

[(1:25)] Lydia Emily: All right. [Laughter]. I, um, have been known to do illegal art here and there. I’ve done mostly legal art, uh, commissioned, hired murals, walls, but there was, there, there have been times where I get a little naughty and go out with my friends and get up on crazy places and, um, so we were in Oakland and Oakland, California, which is like the wild west. Oakland is like a crazy town. Everybody who lives there is a champion because that place is banana pants and so we went out in the night and when you go up on a billboard, um, for anybody who’d like to try this, when you go up on a billboard or an overpass of a freeway, uh, to do street art, um, they use a, a latch to pull down the ladder and if you jump, if you get just right and you jump up, you can release the ladder. So I was doing that and I was gonna go up and do street art with some friends of mine. Like, yeah, I think it’s probably 15 years ago now. Yeah, 15 years ago, and, um, the latch didn’t release, so I jumped up to grab something thinking it was gonna release and it didn’t and as you know, that can pull your arms out or whatever. So I, I felt like a little twinge, but I didn’t think much of it. A couple of weeks later, and it was, it was a good piece of art by the way. That was a lot of fun that night. A couple of weeks later, I started having pain in one of my shoulders. I thought it was associated with an injury, but it was not.

It was, it was MS. I just didn’t know it yet. So I was like, oh, I got an injury being, you know, a rebel or whatever, and look at me, and, um, I did, you know, I went to see the chiropractor, I went to see my doctor. I went to go do all these things. I kept telling people it was an injury. I may have hindered my own progress by trying to tell doctors what I thought it was ’cause I’m a doctor, obviously, and um, so it took a lot longer. But then one morning I woke up and half my tongue was numb, just half and I thought, I’m like, I think I was like 39. I was like, I don’t really fit the stroke profile, but I’ll go to the emergency room and I went to the emergency room and then they kept me and they saw infractions on my, uh, scans and, you know, that’s when I was diagnosed. I was diagnosed in the ER basically and, um, I didn’t really know what MS was. I remember my mom came and she was sitting next to me and the doctor, I actually feel really bad for ER doctors. The ER doctor had to tell me I had MS. I felt so bad for him. I was like, you look so uncomfortable. Like you’re used to sewing people’s hands back on ’cause of fireworks you’re not used to, you know? And, um, I remember when I was saying to him, oh, I’m so sorry. I feel so bad for you. You have to do this. My mom rubbed my back, which we’re not, my mom’s not super emotional or close. So she rubbed my back and then I knew, I was like, oh, this is a bad thing. I should be more worried about me. What is it? And then I had to research, this was before Twitter and you know, all these things. There was the internet, but it wasn’t as keen or insane as it is today. So, you know, we had to, um, go to different doctors and get different advice and try different medicines. It was, those first couple of years were, they were, um, uncharted territory and, and rough, um, trying to get it right.

[(4:58)] Stephanie: Yeah. Very similar to me. I was athletic and 25. So when I, my first symptom was my legs went numb. So naturally I was like, oh, it’s a sports injury. I’ll just ignore it. It’s fine. Obviously, I’m fine and maybe I have a medical background. So I always say I’m good at talking myself out of the fact that things could possibly [inaudible].

[(5:17)] Lydia Emily: Yeah. Yeah. You guys are the worst patients.

[(5:19)] Stephanie: We’re the worst patients. Um, but I remember that same similar feeling of not really being worried about myself, but more about being worried about those around me, and also I was very career-driven, just like you’re very driven by your art. So I was mostly concerned about that, how the MS would impact working and how I perceived myself in the world as it relates to my job, my career, what I’m passionate about and I imagine being an artist, that was one of the first things that hit you.

[(6:05)] Lydia Emily: Yeah, well, I wasn’t, I would, I was just doing a show for when I got diagnosed, I was just in the middle of doing a show for Red Bull, the, the, the drink and, um, we had to fly to Miami and at that time, I don’t think I knew that the heat would affect me so much. I didn’t have any real, there was just no Googling MS then and um, so I flew to Miami and had to paint in the heat at this show and stand there and be presentable and, you know, and all this stuff ’cause Red Bull was nice enough to pick me for, um, a show they were having at Art Basel in, um, Miami at the time and it was, it was brutal. There were so many trips in and out of hospitals of trying to get it right, trying different things out, seeing what works and what doesn’t and so I lost so many opportunities to work, um, provide for my family, my kids. I was a single mom, um, you know, and a single mom with no, um, child support of two kids and one with autism. So losing any work as people know is, uh, you know, life or death and, um, if I hadn’t had the support of a huge support network of Ruffians for sure and my family, but, um, I wouldn’t have, I, we wouldn’t have made it. We wouldn’t have made it as far as we did. We wouldn’t have made it to now. Um, it’s one of the things that I think is so important about organizations that are bringing people together who have MS, Lyme, whatever, you know, cancer groups of people are what pull you through these times.

[(7:48)] Stephanie: Absolutely.

[(7:51)] Lydia Emily: Um, and so that’s what I needed. I needed that group.

[(7:54)] Stephanie: Definitely. Now you mentioned the first two years being quite the rollercoaster, which I definitely relate to. I feel like you’re just figuring out how heat or stress or things affect your symptoms and you’re trying to create space for this new thing that isn’t going anywhere and trying to adapt so that you can do the things you like to do. So tell me a little bit about how you’ve made adaptations in order to continue making art and do you feel like MS has had a negative impact? A positive impact? A little bit of both.

[(8:35)] Lydia Emily: Well, let me think. I would say that MS, I would say that MS has had a total equal parts negative impact and equal parts positive. It is, it is completely equal. I had already been painting a, my, my whole career in art has been about politics. So I’ve been painting about people with disabilities, people, um, who’ve been sexually trafficked, people who have, um, you know, the people I, I’ve never painted. I have a book coming out in a couple of months and I have a chapter called, um, Tints[?] and Flowers and I’ll, I’ll explain it, sorry. Um, there’s this idea that, um, women in general, um, and people in the art world paint tints[?] and flowers, and I never did it and I think it’s why my art career was rough. Up and coming, I was painting about the politics in Afghanistan. I was painting about what was happening in the, you know, the, uh, Dominican Republic and the DRC and people who were suffering from Lyme or people who were marginalized and so that shit just wasn’t popular back then. It’s all the rage now. Everybody’s a keyboard, social justice warrior. But, and um, so I had a really hard time coming up and so painting about multiple sclerosis and making adjustments to how I paint, I feel like, I feel like I’ve been running the race already. Um, like I did a painting a couple of years ago about me with multiple sclerosis, and it’s two mes. One side is me, uh, the way I normally look, and the other side is what I feel like and it, my spine was kind of out and, and there’s no blood or anything, but like the spine is kind of out and, and sandbags in my feet and all these things and I got, um, I got, uh, was the word, my MS takes my words all the time. Um, not notified, but when somebody like reports you, there’s a word for reporting you on the internet, I just can’t click it right now.

But I’ve been reported over and over again for grotesque photography, which is not what it, it was a painting, it wasn’t a photograph. I do paint highly realistically, but it was a painting of what it feel, what it feels like for us and it got taken down everywhere and it’s part of what I feel like is happening with MS right now. There’s tons of these happy ads with young girls going, “I just take an injection once a week,” and la la la. And it’s like, what? That’s, it’s, you know, there’s so many people suffering so badly and need to be seen or, or heard. Um, and these, these depictions of, of what it, what it is not like, ’cause it is not like that. I find, I find not offensive but detrimental to, um, us moving forward. Um, I just really wanted to say that. Those things really bug me.

[(11:48)] Stephanie: Yeah. What adaptations have helped you navigate with MS?

[(11:51)] Lydia Emily: Designs[?] for painting or, so I started, um, early on by tying my kids’ shoelaces to my hands. They had these really cool sparkly pink shoelaces ’cause they were like seven, six and I was like, that’s adorable. So I would tie them to my hands and I would stick the paintbrushes in them so that it would hold it because I have ataxia and I have, I can’t, so I can hold a paintbrush, I can pick up my coffee cup in front of you right now and I can hold a paintbrush, but I can’t hold it for more than a few minutes. The muscles start to give out really fast and then they start to shake and so since I paint things like I paint these, uh, hyper-realistic portraits, people’s eyelashes, the folds on their skin, wrinkles, the things that I love and, um, those things are almost impossible to do with a single hair paintbrush when you have at ataxia.

So when the paint, when the shoelaces stopped working, uh, ’cause they would loosen a lot and they were rough, I started using bra straps. So the inside of a bra strap has this, like, a lot of them have like a coating on the inside that’s almost like a gel and it helps it stick, stay in place and they’re elastic so they stay and they’re very snug, but without cutting off the circulation. So I started using those and I have a lot of paintings that, uh, have those kind of showing in them. You know, self-portraits and things. The adjustments that we’ve had to make in our life are total. Um, my husband is a prop maker, so he’s the best husband to have in this situation, I think, and he’s got a cord-hung, like a bar hung, uh, hung up right now that I’m talking to you on right now that holds the phone because I can hold it for a minute when I’m talking to somebody, but I can’t hold it for a half an hour, hour podcast, having air conditioning everywhere, having the wheelchair ready, whose name is Ellie and canes ready and a ramp already set up in my house.

Even though I don’t use a wheelchair every day, it’s there permanently so that on days when I do need it, it’s there. We don’t have to rush to pull stuff out or feel like we’re in a panic. Things are set up around the house to make my life as easy as possible, which in turn makes my family’s life as easy as possible because they don’t have to worry all the time that I have to hold my phone or I can’t paint or I can’t get around. So for me, setting up, even though we might not need everything yet, setting up for what, what you need, it’s like hoarding food for the storm, right?

[(14:33)] Stephanie: Yeah.

[(14:33)] Lydia Emily: Or toilet paper for COVID.

[(14:35)] Stephanie: 100%.

[(14:36)] Lydia Emily: Yeah.

[(14:36)] Stephanie: And I think that was a pivotal moment for me was when I stopped trying to be the girl on TV who’s skipping around and being like, everything is fine.

[(14:47)] Lydia Emily: Right.

[(14:48)] Stephanie: And actually admitting that I had symptoms that did affect me every single day and do require adaptations and once I finally got over that mindset of adaptations are a sign of weakness to adaptations are a way for me to take my life back and get out to do those things, right? So I don’t-

[(15:11)] Lydia Emily: Adaptations are a sign of strength because without them you have to lean on someone else. With them, you can be more independent and that’s the strongest way you can be.

[(15:21)] Stephanie: 100%. So what advice do you have for someone who may not be in that place yet and who may not wanna use an assisted device or may not wanna ask others for help?

[(15:33)] Lydia Emily: You know, what helped me, now that I think about it, you know, what helped me is I realized I was robbing people of a gift. I was robbing my husband of his gifts. His gift to me was helping create these things or helping, or even if somebody can’t create ’em, buy them, uh, hook them up. They feel good doing that. The person, people around you who you love, they love you. It’s like equivalent to Christmas, they get to set up this thing and give it to you, and then they get to see you use it. That makes them feel good and makes them feel important in your life and if you have somebody that, that doesn’t make you feel good, then you might wanna replace him before you start any other medication ’cause that’s no good. But yeah, you wanna give them the gift of feeling good, feeling useful ’cause they feel useful helping you. I know that I feel useful helping somebody. It, those things are what make us human and so that would be my advice. Give them the gift of helping you.

[(16:42)] Stephanie: Yeah, I 100% agree. And it also feels better to do something even if you need to use an adaptation to do it. If you need to park in that handicap spot, if you need to use your cane, feels better to go out and do it than to stay home and avoid it.

[(17:00)] Lydia Emily: Oh girl, I got that handicap placard the minute they let me have it. Even on days when I’m walking, I’m like handicap, handicap, placard. I’m gonna use it. Yeah. So absolutely.

[(17:07)] Stephanie: You gotta save your energy. I understand.

[(17:10)] Lydia Emily: Gotta save my energy. If I don’t use it, then I might be tired later and I won’t be able to do whatever else I wanted to do. Yeah. No, I, I take all the things I’m like, just pour ’em on me.

[(17:20)] Stephanie: Exactly and I think that’s important too, is even if you feel a little, maybe a little overconfident, like you don’t need the assistive device or don’t need the adaptation, we learn from our mistakes and we learn from the days where we push too hard and we don’t use the things we should use and then we pay for it.

[(17:38)] Lydia Emily: Right and then you pay for it later and then you have-

[(17:39)] Stephanie: Absolutely.

[(17:40)] Lydia Emily: And then you have everybody around you. That’s the worst when you have people around you going, I told you to use your cane, I told you. Yeah, I don’t wanna hear any of that. I’ll just use it so I don’t have to hear I told you so. So that’s the worst [laughter].

[(17:51)] Stephanie: That is the worst. Now for those of, uh, our listeners who haven’t already seen it or heard about it, your documentary is called The Art of Rebellion and I think you told us a little bit about the rebellious side, but you’ve also told me in the past that you feel or you absolutely refuse to feel ashamed about your diagnosis and you even said that you try to make having a disability as fun as possible.

[(18:18)] Lydia Emily: Yeah. I mean, why, why would I feel I, I’m not speaking for anybody else, but why would I, me, Lydia Emily, feel ashamed about anything? There’s, there’s two ways that I look at it. One, it just adds to my greatness. I would like to say that. This, all the, everything that happens to me just adds to my greatness and that’s what makes, and that’s me being funny. That’s just funny. Like, it’s so completely preposterous that I would have cancer and MS. So, um, I don’t, I don’t feel any shame. There’s the shame I would feel would be, I also find my MS to be a gift in a way that if you look at, so my daughter’s in physics and, and everybody in the house is into statistics and physics. So if you look at your group of people, right? So let’s say I have a group of 10 really close friends, really close friends, right?

And we have ’em over for barbecues or whatever. They’re the people in your little orbit, right? Statistically, a percentage of them are gonna get an autoimmune disease. Statistically, a percentage of them are gonna get cancer, uh, suffer, uh, you know, some sort of, uh, aggressive attack, you know, something like that. So I, I can say I’ve taken that from my 10. I’ve taken the cancer, I’ve taken the MS. I’ve lowered the chances statistically of one of them getting it and so that makes me feel really good. I, I, I’m so happy ’cause I love them and I don’t want anything bad to happen to anybody. So that’s one way of looking at it, you know, that’s one way that helps me feel like, I mean, I don’t believe there’s any meant to be, but in, ’cause I don’t believe in mystic stuff but for statistics, for my math brain, it was meant to be that one of us was gonna get it.

So let it be me. I can handle it and let them be able to walk and let them be able to have, you know, the things that I can’t have ’cause I get to have other things and I feel no shame and I feel no embarrassment, um, and absorbing my strength and feeling proud and standing up with it takes it away from other people to maybe feel pity for me. You know, when I stand up tall, I’m like, “Yeah, I’ve got MS.” So like, you know, everybody’s got something, this is mine. I wear it with a badge and these are the accommodations I’ve made for it and this is how I choose to live my life knowing what it, what is happening, knowing what it’s gonna be and you kind of rob anybody from feeling pity.

[(20:56)] Stephanie: Yeah, I have found the same thing. I learned that very early on. The way I present my MS to the world is the way I receive responses back. So if I am just like you are, I have MS. It affects me. I have to make changes to my life because of it. Now look at all the cool things I’ve done.

[(21:19)] Lydia Emily: Yeah. Now look at, look at all the things I’m trying to do and all the cool things I’ve done could be reading. You know, not everybody’s an artist or a mathematician or, you know, not everybody’s a researcher. So when I say like, I’m still doing things, it, it doesn’t, those things don’t have to be climbing a mountain. Those things could just be reading, knitting, the things I see people doing with MS, the artists I see putting up art who are blind. I mean, I’m only blind in one eye from MS, but who are totally blind from MS and they’re drawing still, you know, or writing, like being prolific isn’t about your accomplishment. You don’t, I don’t have to paint 1,000 paintings about MS. I don’t need to be prolific to be accomplished. I could just do one thing and that one thing is fine and having pride in that one thing is all that matters. We, I just recently judged an art contest for people with MS all over the world.

It was called, I don’t know, World MS Day, something. Um, so it was an art contest for people who had MS all over the planet and we took, um, entries from the Middle East, from South America from, and, and the entries were completely different. So you have people who obviously had gone to art school of some kind or had some inherent natural talent, and then you had people who could just barely, you know, use crayons and, and that turned it in on a napkin from a, from a restaurant. Their stories are different and what they’re able to do with their MS and how it affects them is different. What they’re able to accomplish is different. But it, it was about what they were trying to say, what they were trying to relay made everything about the piece of art possible and people won and, and got into the finals that had no training. They were just able to find a way to express themselves, you know, and that’s, that’s really what it’s all about. It’s not about whether or not you end up in a magazine

[(23:23)] Stephanie: 100%. I think it’s about recognizing that MS or any challenge changes fundamentally who we are, whether we’d like to admit that or not, and-

[(23:35)] Lydia Emily: Absolutely. I mean, look at, I was, I was jumping around on freeways 15 years ago, you know, my life is completely different, completely different. And I thought I had all the time in the world and all the, all the energy in the world and I don’t. Now I paint maybe one painting a year, a year, and that’s fine. That’s who I am and that’s, and people wait for it.

[(24:01)] Stephanie: And sometimes I feel like what I am able to do, I’m now all that much more proud of ’cause I mean, I did-

[(24:09)] Lydia Emily: Yeah.

[(24:10)] Stephanie: I was more prolific before MS but now the things that I pour my energy and my intention into are things that I am much more exponentially proud of.

[(24:23)] Lydia Emily: ‘Cause of all the effort it took and the concentration and everything. Yeah. No, absolutely.

[(24:30)] Stephanie: Is there anything else you’d like to tell us about your art?

[(24:33)] Lydia Emily: Art? Doing art for me, as somebody with a disability doing art, there’s a catharsis to it that forces you to meditate even if you don’t meditate. Like, I don’t meditate, I don’t sit down and do any of that stuff. But when you’re focusing that hard on something, there is a meditation to it and the fact that you are taking the time to care for yourself to do it is just worth everything. I don’t even see my murals. One time I painted a mural in Skid Row in Los Angeles. It was a tough neighborhood, let me tell you and we had a lot of tough moments. I painted the mural. It’s two stories, took some pictures, left, um, got out. Um, and it, it’s, it’s not mine anymore. It doesn’t belong to me anymore. It belongs to that neighborhood and I was, there’s no better point made.

I drove by it once and I was like, ”Hey, it’s still riding”. Uh, riding by the way is a street art terminology for it’s still up. It hasn’t been graffitied on, it hasn’t, it’s, you know, it’s still riding. So it was a year later it was still riding. Although Skid Row, you don’t get a lot of people going and covering people’s stuff ’cause it’s, it’s dangerous. So I drove by and I was like, “Oh, look at that. It’s still riding.” And this guy, I went to take a picture with my phone, um, and this guy ran up to the car and he is like, “You wanna take a picture of that? $5” And I was like, “Oh, well.” He’s like, “That’s my mural. This is, this is my block. That’s my mural. This is our neighborhood. You have-” and I was like, “You are absolutely right. You’re- Here’s $5. I won’t, I won’t take any pictures. I’m sorry.” And I left and that, but that’s it. Like, he didn’t know I painted it. It’s not mine. So it, it’s nothing to be like intimidated by ’cause it doesn’t belong to me the minute I walk away from it. Sometimes they’ll even go and cover your name up and that’s fine. There’s there’s no, like, I did it for the neighborhood. I left it for the neighborhood. There is no pride you get to take with it other than the one you keep to yourself. So, um, when people come up to me and they say, oh, I just do this little knitting, or I just, I made a little- one woman was making cards, so cool. It was in Boston and she had little stamps set and she’s just stamping cards and then writing nice things in ’em. She’s like, they’re just cards. I’m like, this is awesome and you had to buy the things to make it and you had to plan it out. I know how much planning went into it. It’s not just a little card. It’s your effort, it’s your art and I’ll treasure it and I still have it.

[(27:05)] Stephanie: We’re gonna share your website. Do you wanna share the book that’s coming out soon?

[(27:10)] Lydia Emily: Um, yeah. The Art of Hope and um, it’s a, takes from the name of the documentary a little bit, um, the Art of Rebellion. But Art of Hope is about, it has less art than it does words. It’s not like an art coffee table book. Um, it’s about me and some parts of my life are in it, some parts are not. It’s my first book and it’s also about how to get along in the healthcare system in the United States when you don’t have insurance. Um, it’s about how drugs are priced. It’s about the art world, which is rubbish, and it’s about MS and, um, and love and still finding hope and it’s about, it’s about getting past our differences, I hope. I wrote a passage in the book about, sometimes you can only agree on gardening, and sometimes for me, you can only agree on art and the work ethic that comes with those long hours standing in the street painting. Who we are at our core is bigger than the shirt we, the t-shirt we wear with the logo on it. You know?

[(28:25)] Stephanie: Yeah.

[(28:25)] Lydia: I hope that’s a good explanation.

[(28:27)] Stephanie: And being united for a purpose.

[(28:30)] Lydia Emily: For a purpose.

[(28:31)] Stephanie: Helps you overcome almost anything, I think.

[(28:34)] Lydia Emily: And having the respect of my fellow man that even if I completely disagree with every, fundamentally with everything they say and they with me, we can still love each other.

[(28:47)] Stephanie: Absolutely and it’s not like MS is very nice to us, but we find a way to get along with it.

[(28:51)] Lydia Emily: I know.

[(28:53)] Stephanie: Lydia Emily, thank you so much for sharing your story, your experiences, and approach to MS with us today. We’re so happy that you joined us.

[Music]

[(29:01)] Lydia Emily: Oh, thank you so much for having me. It’s been a pleasure to be here and I can’t wait to come up and take you guys spray painting.

[(29:11)] Stephanie: Thank you for tuning into this episode of the Can Do MS podcast. If you’d like to check out Lydia Emily’s artwork, you’ll find a link to her website in the description of this podcast episode. We’d like to thank Biogen and all our generous sponsors for their support of the Can Do MS podcast. Until next time, be well and have a great day.

[Music]

[END]

This podcast transcript is made possible thanks to the generous support of the following sponsors:

Learn More...